Michael Leunig (1945–2024)

Michael Leunig was born in East Melbourne on 2 June 1945, the second eldest of five children in a working class family. His father was a slaughterman, and his mother was a tea lady at the same abattoir. His early life unfolded in the industrial western suburbs of Melbourne – Footscray, Maribyrnong and beyond – among factory gates, paddocks, rubbish tips, kitchen tables and abattoirs. Deaf in one ear from birth, he attended Footscray North Primary School and Maribyrnong High, though his deeper education took place elsewhere: in puddles, loopholes, quiet observations, and the ordinary poetry of street corners.

As a boy he was captivated by Enid Blyton, Arthur Mee and Phantom comics, and later drew sustenance from the Book of Common Prayer, J.D. Salinger, Spike Milligan, Bruce Petty, Martin Sharp, Private Eye magazine and The Beatles. These influences – by turns sacred, absurd, soulful and satirical – helped shape the unique artistic voice he would become known for: tender, mischievous, melancholic and wise.

In 1965, during the Vietnam War, Leunig received notice of military conscription from the Australian government. His rejection – due to partial deafness – was a stroke of fate that deepened his pacifist convictions and steered him away from institutional life altogether. He fled formal education and embraced a quiet, gritty existence working as a factory labourer and meatworker. All the while, he nurtured a private practice of drawing and reflection.

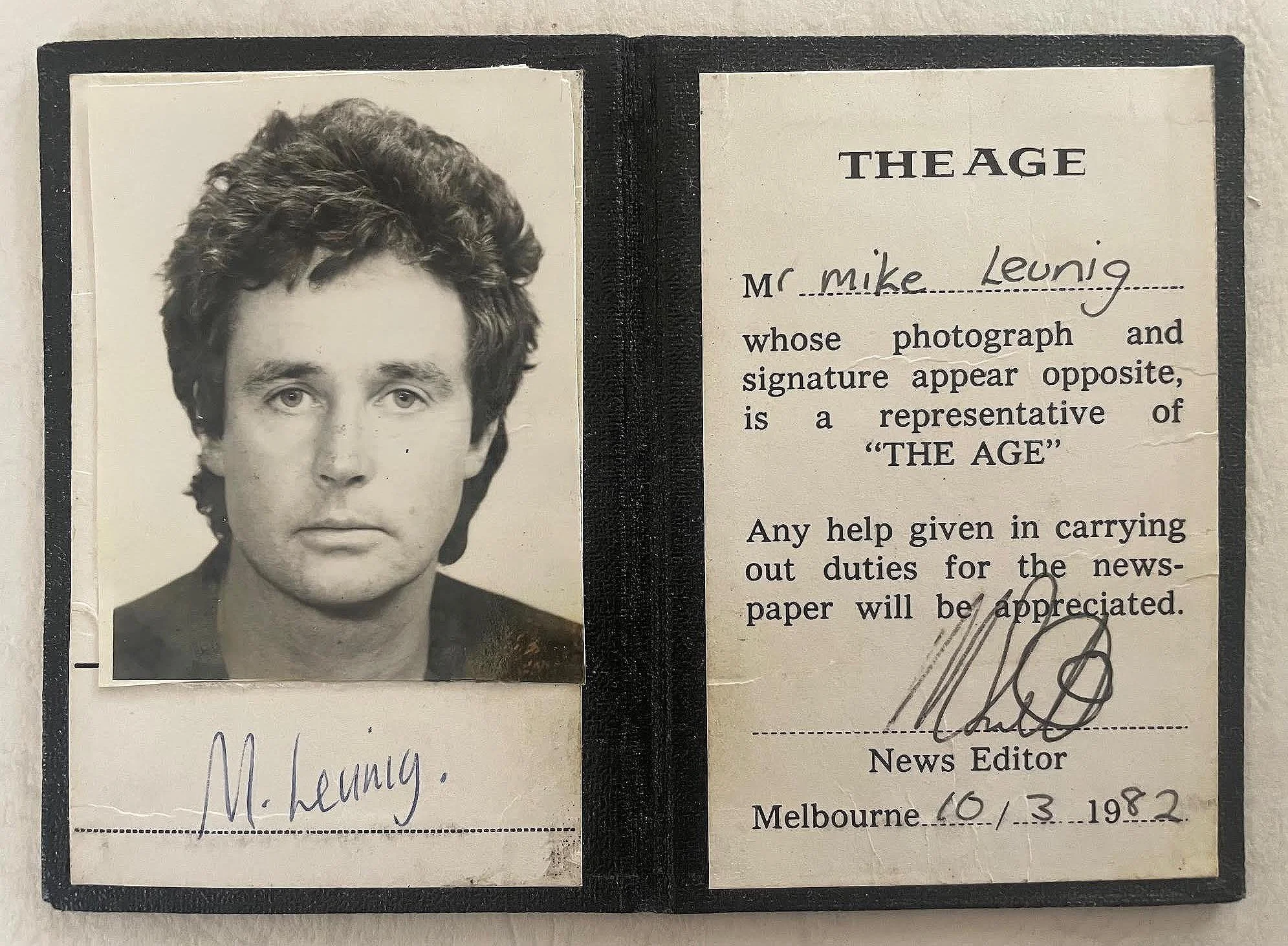

His first cartoons appeared in Lot’s Wife at Monash University, and from there he began contributing to the Nation Review – a fiercely independent, satirical weekly that became an influential home for his early work. In that irreverent, countercultural publication, his poetic and subversive drawings developed a cult following, cutting through the conservatism of the time and drawing wider attention. This success led to him submitting work to The Age in 1969, the beginning of a five decade presence in Australian newspapers, where his work became a regular and defining feature.

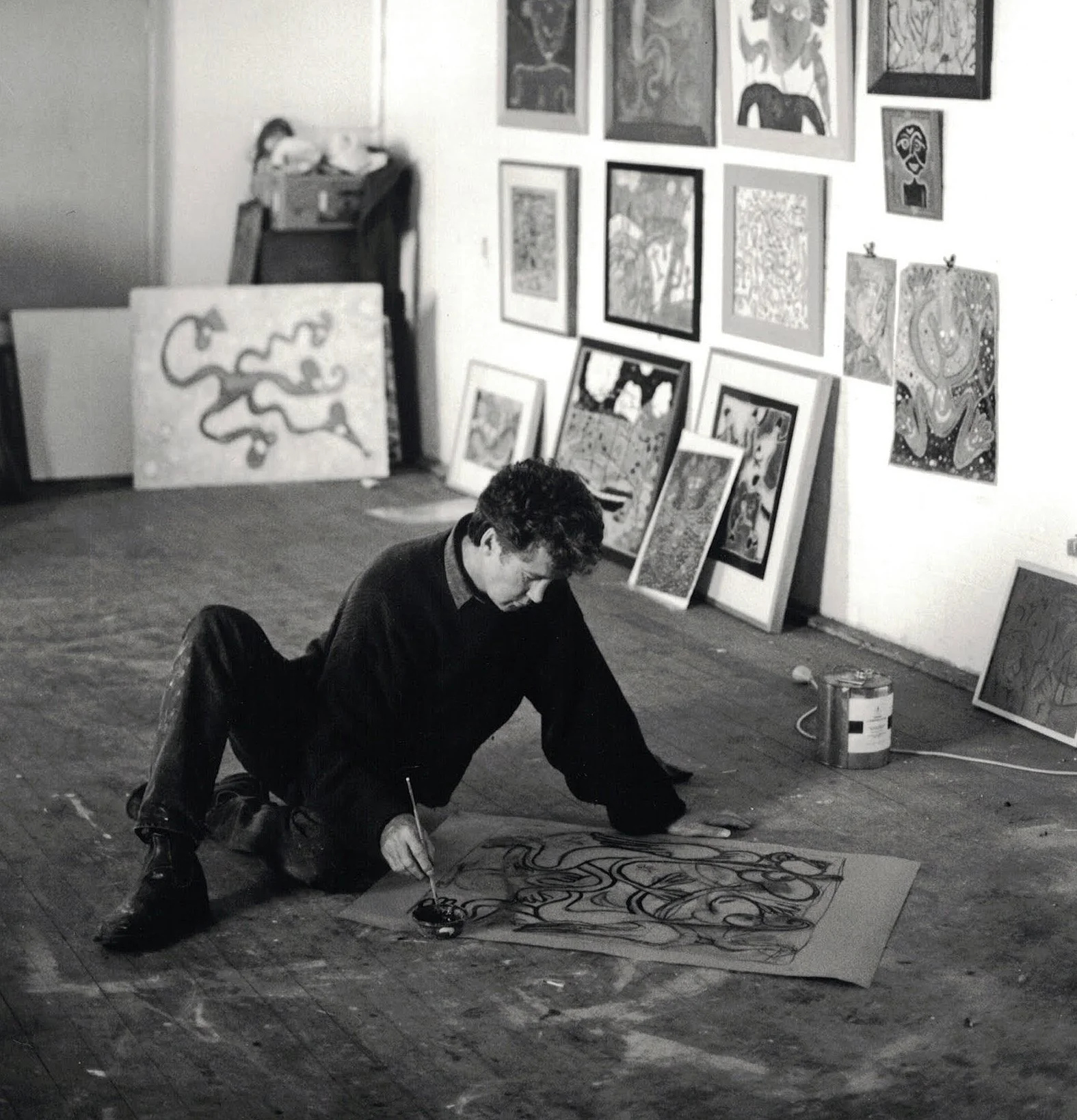

His first book, The Penguin Leunig, was published in 1974, and over the years he released more than twenty three collections of cartoons, poetry, essays and prayers. His characters – Mr Curly, Vasco Pyjama, the duck and the ever present moon – became beloved icons of a more lyrical, vulnerable kind of cartooning. Their concerns were spiritual, emotional, and disarmingly human.

Leunig’s work was not confined to the page. He collaborated with musicians and poets, creating and performing at venues including the Sydney Opera House and London’s National Theatre. He worked with the Australian Chamber Orchestra on productions like Carnival of the Animals and Parables, Lullabies and Secrets, and co-created the musical project Billy the Rabbit with Gyan, featuring contributions from Paul Kelly. His imagery also shaped the creative direction of the 2006 Melbourne Commonwealth Games opening ceremony, which included a performer in a duck costume inspired by one of his poems and a symbolic flying tram. He was a guest of honour at festivals, churches, protests and concert halls, and once shared a stage with the Archbishop of Canterbury. For a cartoonist, he got around.

In 1999, he was named a National Living Treasure by the National Trust of Australia, and was later awarded honorary doctorates from La Trobe University, Griffith University and the Australian Catholic University for his singular contribution to Australian culture.

He often said that he felt out of step with his times – and sometimes his times agreed. During the War on Terror, Leunig’s fierce opposition to the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq made him a lightning rod for criticism. As Australia’s political discourse hardened, he found himself increasingly alienated from its culture of noise, hostility and certainty. The whimsical softness of his early cartoons gave way to darker, more haunted work. Mr Curly and Vasco Pyjama all but vanished for a time. But the duck never completely left, and the moon remained – a distant, faithful witness in the skies of his drawings.

In later years, Leunig’s work continued to stir both deep affection and occasional controversy. He questioned the direction of social norms, sometimes clashing with public sentiment around issues such as vaccination, parenting and identity. In 2022, his long-running position as a regular cartoonist at The Age came to an end. Officially attributed to concerns about audience disconnect, the decision came amid discomfort with some of his more politically direct work – including his outspoken opposition to Israel’s long running blockade and assault on Gaza, and the broader occupation of Palestine – issues he had expressed deep concern about for decades.

Despite his departure from mainstream media, his work continued to be published, exhibited and shared. He remained – right to the end – a cultural presence, albeit one increasingly outside the institutions he had once helped define.

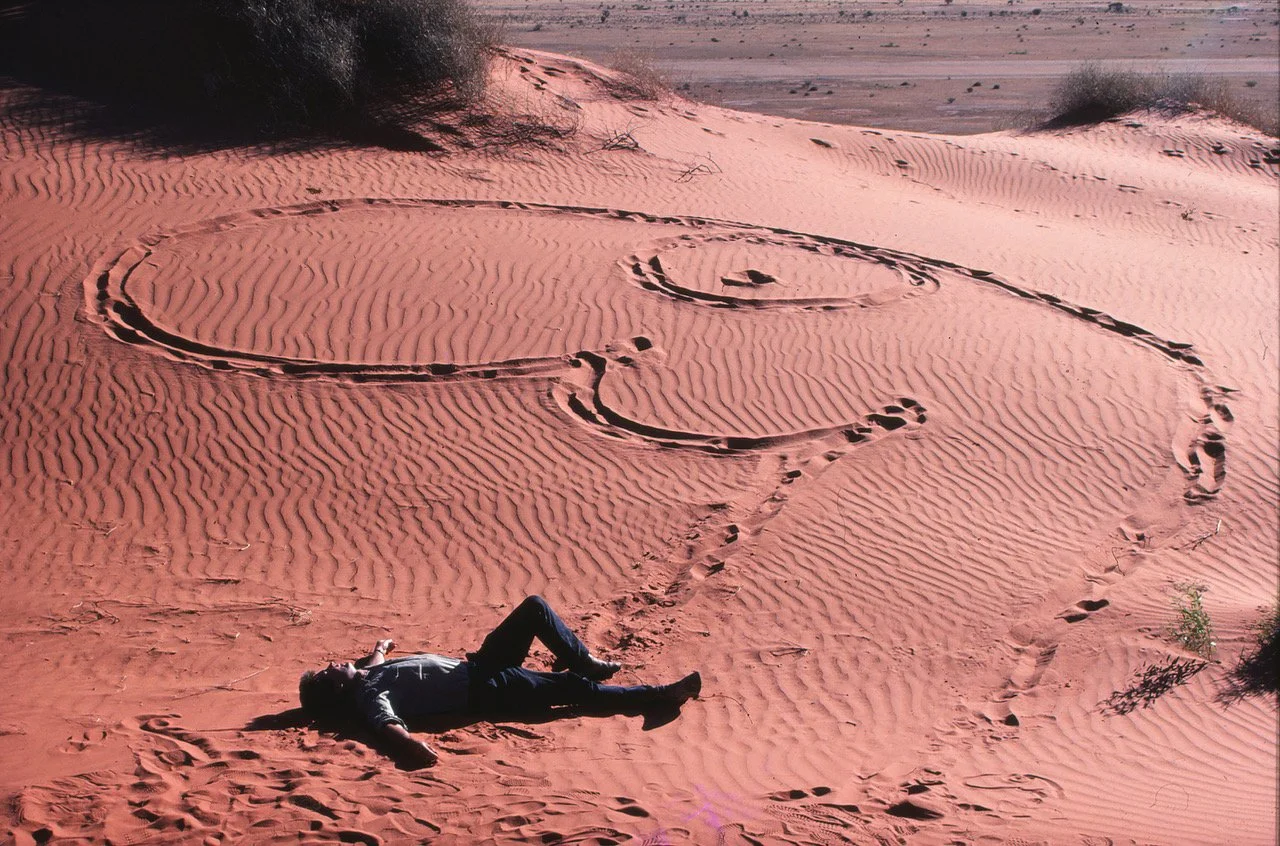

The father of four children, he spent his final years mostly in the solitude of the northern Victorian countryside, walking among the trees, tending to his thoughts, and occasionally returning to Melbourne for coffee, conversation and chamber music. He remained, throughout his life, devoted to nature, to beauty, to humour and heartbreak, absurdity and grace, mystery and kindness. He believed in the soul, in silence, and in small things that matter.

Michael Leunig died peacefully on 19 December 2024. His drawings, poems and prayers continue to echo in hearts and households across Australia and far beyond. He leaves behind a legacy that resists categorisation: a body of work that softened the news, disarmed the powerful, bewildered the cynical, and gave voice to a deep, enduring kind of tenderness.

The duck walks on. The moon still shines.